Archives For:

Posts

A Legacy Rooted in Passion: Jim Scheff

It is with great love and appreciation that Kentucky Heartwood would like to announce the departure of Staff Ecologist Jim Scheff. Jim’s legacy reshaped the dialogue about forests in Kentucky…

Opposition to Big Hill Line Transmission – Berea, KY

September 2, 2025 President Cheryl L. NixonBerea College – Office of Academic Affairs210 Lincoln Hall Berea, KY 40404 Dear President Nixon I write to express my strong support for Berea…

May Tornado Damage Analysis

On May 16, 2025, a powerful tornado left a nearly 60-mile track of severe damage from Somerset to London. Nineteen people died, scores were injured, and homes were destroyed. With…

Jellico Comment Period Debrief

Thank you to our members, donors, and supporters for answering our call to action for public comments! During the 30-day comment period for the Draft Environmental Analysis (EA), almost 700…

U.S. Forest Service Pushes Massive Logging Project on Daniel Boone National Forest in Spite of Public Feedback and Biden’s Executive Order to Preserve Mature and Old-Growth Forests

For Immediate Release The U.S. Forest Service has released its Draft Environmental Assessment for the Jellico Vegetation Management Project, which would log 10,000 acres of the Jellico mountains in southeastern…

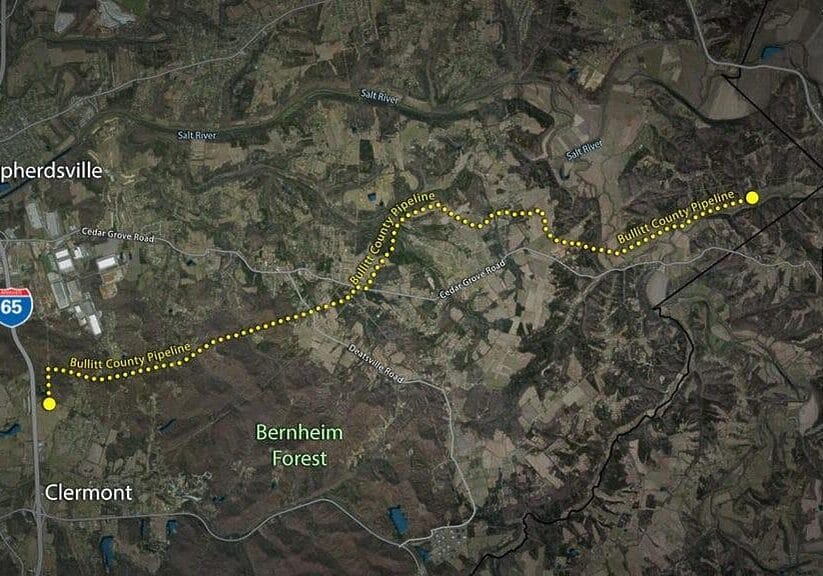

SAVE BERNHEIM – STOP THE PIPELINE!

UPDATE: Kentucky Lantern Article – 5/20/24 Bernheim Forest appeals to Kentucky Supreme Court to stop pipeline in conservation easement Dear Kentucky Heartwood members, I am reaching out to you today…

Thank you to Old-Growth Science Summit donors!

Donors and Supporters, I want to thank everyone who donated to help get me to Washington D.C. to attend the Mature and Old Growth (MOG) Science Summit. The conference had…

5,000 acre logging project proposed north of Morehead along the Sheltowee Trace National Recreation Trail.

The Daniel Boone National Forest has proposed a 5,000 acre logging project just north of Morehead along the Sheltowee Trace National Recreation Trail. While this project is problematic on many levels,…